On View: March 11

In anticipation of our 50th anniversary in 2021, The Kitchen has initiated a series of conversations among artists across generations who will discuss their work and their perspectives on The Kitchen’s evolving role in the cultural landscape. These exchanges create opportunities to draw out connections within The Kitchen’s community and to reflect on the organization’s history through the lens of first-hand accounts.

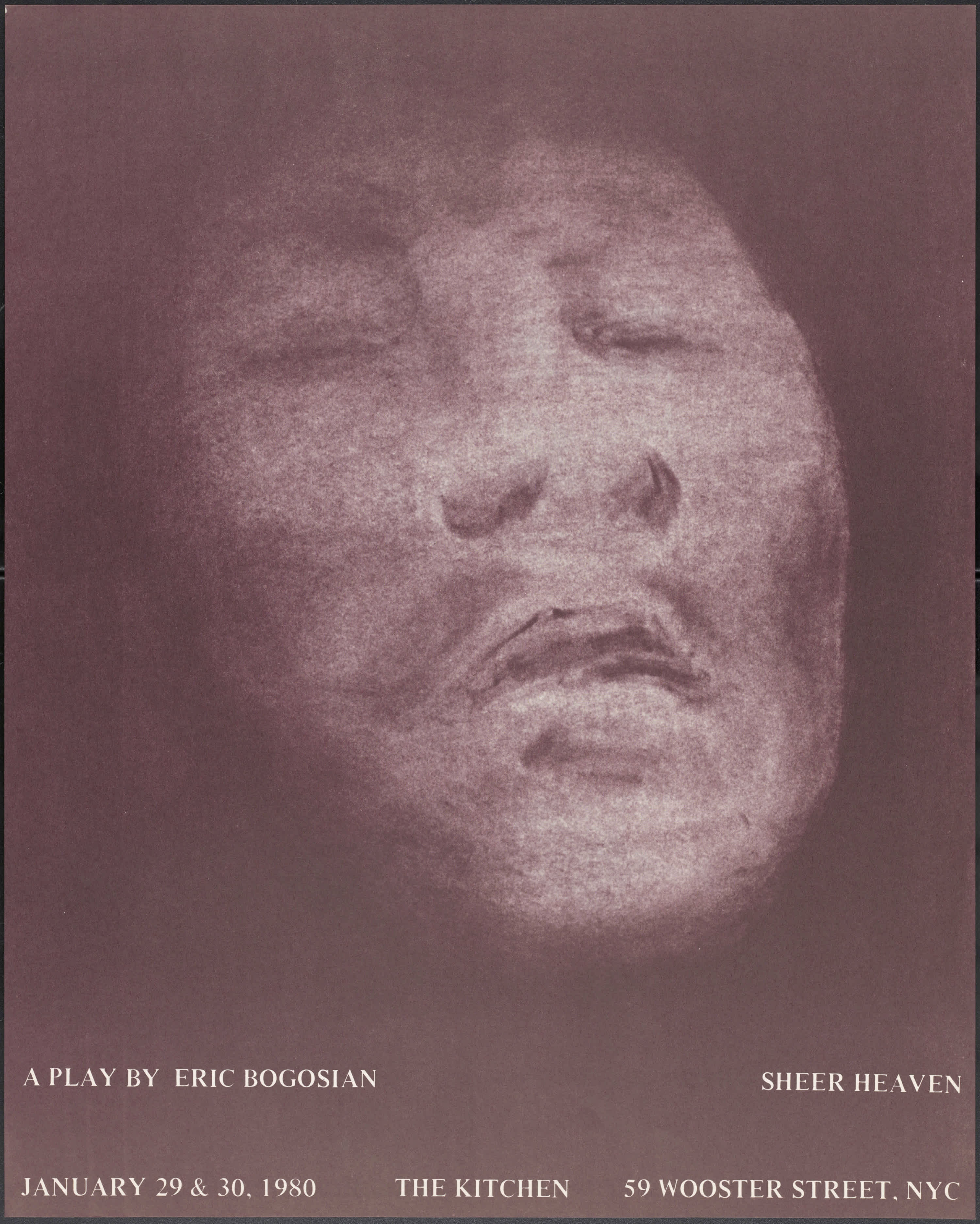

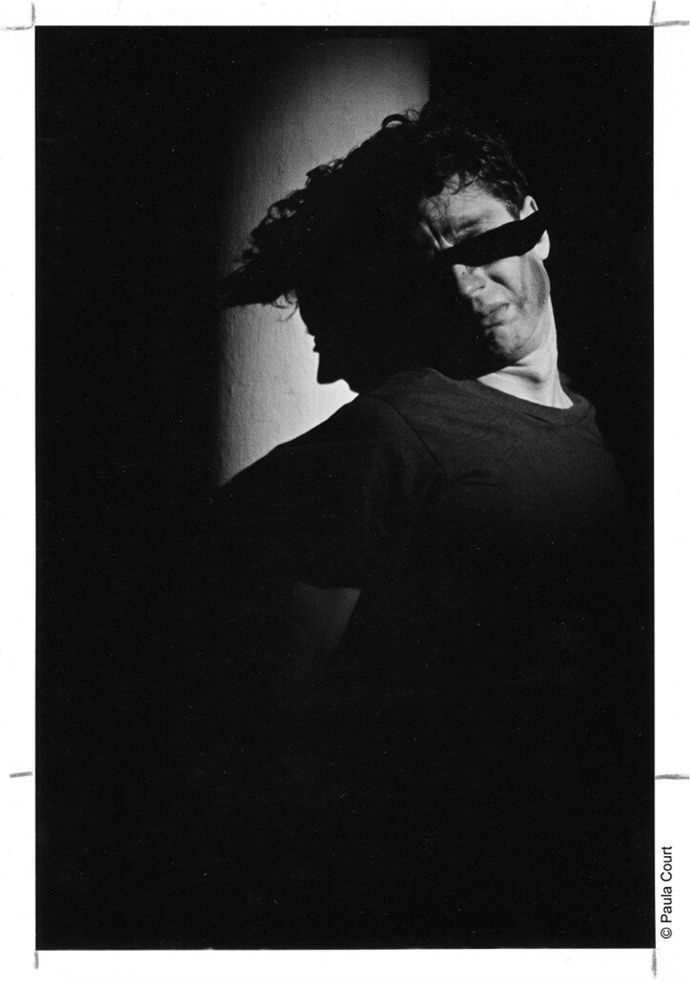

The following conversation took place over email between Eric Bogosian and Tina Satter. Bogosian was The Kitchen’s first Dance Curator from 1978–1981. He also presented several of his own performance works at The Kitchen, including Sheer Heaven (1980) and Men in Dark Times (1982), and premiered works made in collaboration with other artists, such as I Saw The Seven Angels (1984) with Glenn Branca and Michael Zwack. Satter has been involved with The Kitchen in various ways in recent years, working with her company Half Straddle to present the shows Ancient Lives (2015) and Is This A Room (2019) and to organize an installation and colloquy called Here I Go, pt. 2 of You (2017) as part of The Kitchen L.A.B. Conference: Position (2017).

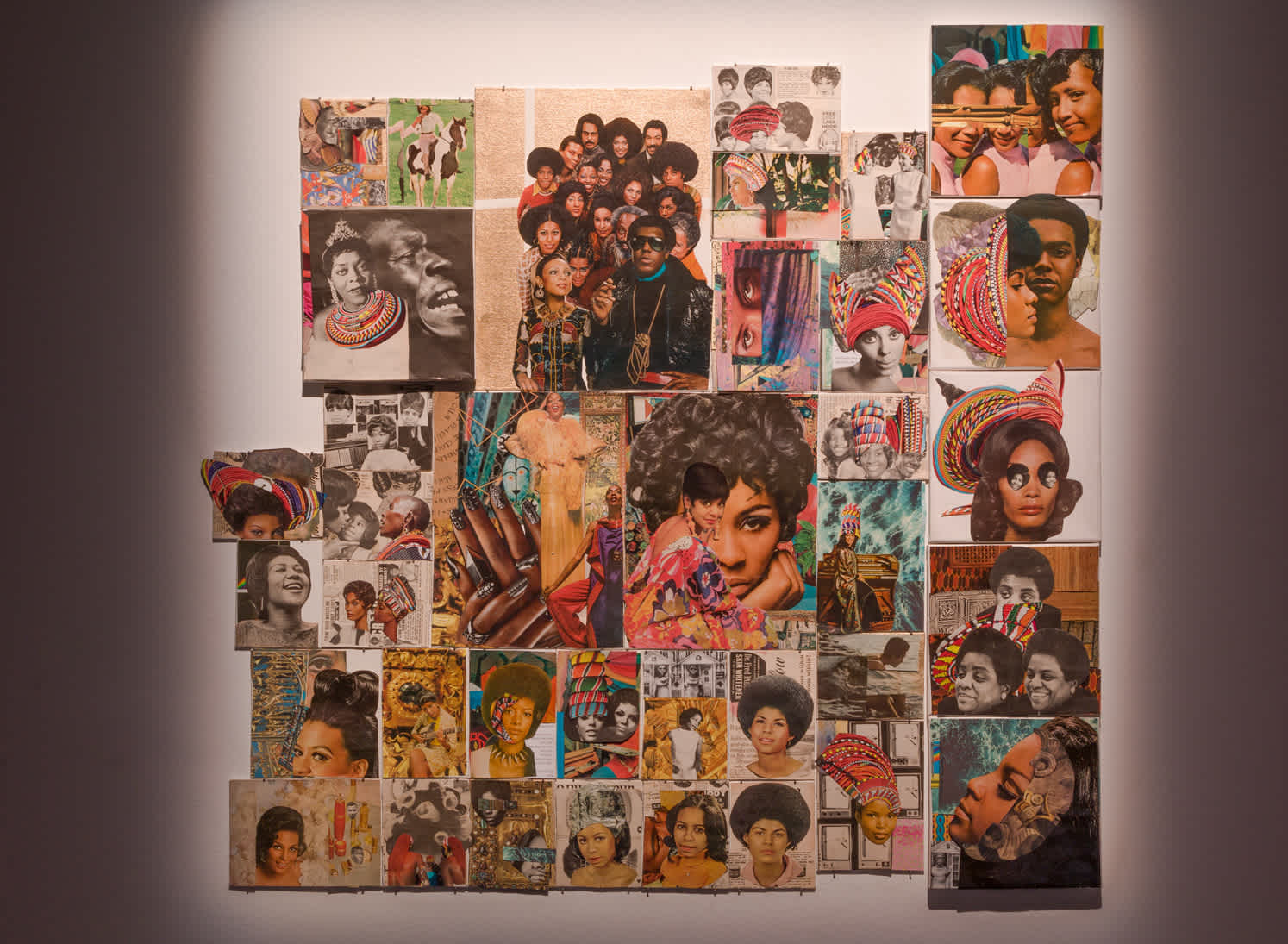

This event is the third in the series of 50th Anniversary Conversations. The previous programs featured Dara Birnbaum and Sondra Perry and Moor Mother and Vernon Reid.

Eric Bogosian: I was a theater major who—almost accidentally—got a job at The Kitchen when it was just beginning and when it was located in Soho. For me, working there was a crash course on the performance art, dance, and music prevalent below 14th Street in the ‘70s. As a trained actor, it was a very different tradition to what I had been exposed to before coming to New York.

My time at The Kitchen was essential to how I ended up making work. Though we all start out wanting to do one thing—I wanted to make Richard Foreman-esque theater—we drift or recalibrate and everyone eventually figures out their “song to sing.” I made one thing, understood it, and then moved on to another thing.

At The Kitchen, I collided with a gaggle of artists who were later labeled the “Pictures” artists. Though most of this “gang” were not performance artists, performance artists and artists working in expanded media were a significant influence for them. Vito Acconci, Jack Goldstein, Lawrence Weiner, and even Nam June Paik all affected the way this group ended up looking at art. It was an aesthetic posture. But it was not “pure” because when we all got to the city other groups had an influence on our nascent aesthetic—people who liked fun, camp stuff for example, and punk rock.

I was very influenced by the “Pictures” gang. Underlying all of our work was the notion that imagery—constructed and non-constructed—suffuses our lives, and we were all very interested in archetype. The member of this gang and the person whose work falls closest to mine is/was Cindy Sherman, whose first show was at The Kitchen [Untitled Film Stills, on view from March 18–29, 1980]. We formulated our approach around the same time and in conversation with the same people. And so, early on I was trying to make “pictures.” Sheer Heaven (1980) was a “play” inspired by Jack Gelber’s The Connection. In order to emphasize the visual aspect, I cast it with an all-Latinx group of actors who in turn translated my script from English to Spanish that my “anglo” audience would not be able to easily understand. I thought of the piece as an foreign movie without subtitles onstage. Likewise, The New World (1980) was a series of visual tableaux, with an emphasis on archetype, alternating between “sweet” or Norman Rockwell-type visual imagery and the “dark” imagery of the streets of New York or of violent movies. The language was meant to be decoration: the point was the image. Men Inside (1981) was a gallery of “snapshots” of different archetypical men. This staged work was close to what Cindy was doing with still photography at the time.

Tina, you’ve also taken cues from visual art and artists. How do you come to terms with the fact that live theater involves time and the presence of the audience? Visual art is static. Theater creates a feedback loop with the audience. Does that change the way the visual operates in your work?

Tina Satter: The artists Jess Barbagallo (actor, writer, art writer), Casey Llewellyn (playwright), and I got thrown into a last-minute conversation at that Here I Go colloquy I did at The Kitchen in 2017 because there was a huge snowstorm, and the scheduled speaker Claudia Rankine couldn’t make it. Casey said something about how she wants her work to operate on an audience, impelling them to do something, or to be in direct relationship to what the audience needed. Without thinking, I said, “I don’t care about the audience at all.” Then that felt like something I had to interrogate more. And in part I know I meant that the work is not designed ever to activate something specific—I am only worried about what is going on in our bubble on stage. Of course that can’t be—or shouldn’t be—true, if I’m working in a field that is literally live bodies in front of other live bodies.

But Jess, who is one of my closest collaborators and super smart, said that made a lot of sense to him, since I’d spent so much time as an athlete playing team sports. (I’d been a serious field hockey player.) And, I think there is something in that. I’ve always felt a deep affinity between the kind of effort and work and stakes at play in field hockey and the energy required to rehearse and put on a play with people. And when you play any team sport, if for one second you thought about what the people on the sidelines were seeing as they watched, you’d be terrible. You just have to be totally present and do the game—or make the play onstage. It’s something more than just actors staying with each other onstage, it is about the fact that we’re doing this here … and you can watch. I of course want and hope it will activate heart cells, maybe brain cells, but what happens if and when those get activated should be totally singular to that person watching.

But visual art usually gets to be present fully on its own terms, and then humans look at and get to have a range of emotions and ideas from it. Jess also said something once like, “no one looks at a Rothko, for example, and says ‘that’s confusing, what is it?!’” We let the incredible abstraction and the specificity of its abstraction be something. I hope for my work—which does have characters saying sentences to each other and is not totally abstract at all—that we’d allow that kind of space where it becomes something to each of us and that we get to see in it what we want. And that kind of energy exchange/feedback loop of not knowing exactly what you are seeing or not seeing something served up to you in the ways you expect to see something is the most exciting and potentially small thing that art can do on the level of molecular change.

EB: Picking up on the topic of audience response or interaction, it is relevant to note that I look to Chekhov for inspiration—I write what’s around me. That’s the hardest thing to do. Especially since the audience for theater (even for plays by Black playwrights) is primarily white and middle-class, I would like to talk about what’s going on with this middle-class, middle-brow audience. This goes back to bedrock fundamentals in my aesthetic, that art is about changing “ways of seeing.” If an artist can expand the way folks see things, then fundamental changes in action might follow. Dictating action does not engender change. Only changing a way of thinking can do that.

If a playwright is writing for a community and its issues, does that naturally make the work (and the audience it attracts) parochial? In other words, there is an issue for a community (say “Black Lives Matter”), but the only people who come to see this work are people who are already “on the side of” the playwright. The people you want to see and hear this play will never come to see it! It’s so hard for work to cross-over. I remember when my mother, who was a very nice person, saw the film Philadelphia because Tom Hanks was in it and came away with a new understanding of the AIDS crisis. (Mom: “I didn't realize those people had it so hard!”) I felt at the time that the film was a huge success in that regard. But so rare!

TS: Yes, there is an insularity to a certain audience that I find both exciting and deeply limiting. When we started showing Half Straddle’s work more widely at places like PS122 and The Kitchen, there were art girls and queer younger audiences saying “I never see myself or these kind of stories on stage like this.” Our attention to detail and aesthetic with the kind of femme-y punk edges was very exciting to them, and in turn it was exciting to be putting something out that filled that void for certain people. So, that’s really been our base, and it is very circular, because it is who we are. But Parker Lutz, the set designer I work with, took a friend to see Is This A Room midway through the Vineyard Theatre run and texted me after that the audience now was a mix of “cool lesbians and old people.” And, I thought “yep, we’re expanding!”

EB: What does “experimental” mean to you? How do we define “pushing form,” and why do that at all? To play devil’s advocate, hasn’t a “style” evolved in the fringe performance scene that occludes the content of the theatrical event by representing the work as “experimental”? In other words, does “avant-garde” mean non-linear, weird, flat, purposely hard to swallow? What made me love Is This A Room was that it rose above the trappings of “weird experimental” and led with concrete, significant content. In other words, it said something, it gave the audience something to chew on besides a weird ninety minutes. Not to mention awesome performances.

TS: I often co-teach a class at NYU with Paul Lazar called “Downtown Theatre,” which is supposed to be a survey of the American avant-garde from the ‘70s to now. It is fascinating to parse with ourselves and those undergrads the semantics of “experimental” and “avant-garde” and “downtown,” and the old chestnut “Is the avant-garde dead??” But what we try purposefully to do is talk about work that—in very general terms—is not “mainstream” and of the Aristotelian structure seen most often at Off-Broadway and Broadway theaters. And we try to discuss the value system of how the art is made, which is that it definitely is NOT supposed to be “weird just to be weird” and “hard to understand.” Instead, it is that the “experimental theater” context allows one to play with the form, to experiment, to take the rigor of the well-made play and expand or undo or serialize it, to consider plot happening in different ways, to consider sets that are not always literal, and to not always approach acting psychologically.

Is This A Room was exciting to work on because we had the text (every word in order that was on the actual transcript), and we had incredible actors who were going to give straightforward naturalistic reads of that text (which to me actually felt like an experimental choice compared to some of my past work). I knew a set would just distract from the energy exchanges and tension of Reality Winner in that moment of the day we were staging, so I made what is the kind of “weird” choice to not have a set showing her house or something. What was kind of ironic was that to make that transcript text hold I had to impose a three-act structure on it: that was wildly helpful for me and the actors, and then for the design choices. It’s definitely the first time I’ve looked to such a traditional frame to hold my plot. So that work came to feel like this kind of potent mash-up of the rigor of trying to stage content not just on one’s own terms, but in terms that best communicate and show that one afternoon and one young woman in it. The piece drew from several genres of style and tradition, but ultimately it still is situated as “experimental” because it is a not “normal” theater text and because we set up a specific movement score and an abstracted set to hold it.

EB: My concerns are that the “downtown” aesthetic has become a brand promulgated by college professors of performance art who indoctrinate young audiences to accept non-linear, untraditional staging as a style. It’s hard for me to put this thought into words, but do you see at all what I’m trying to say here?

TS: I do hear what you’re saying here. I just personally don’t know what is coming up in the vein of “downtown” work now. It’s a landscape that has literally and in theory changed/dissipated. I still get asked regularly to coffees with younger theatermakers who want to know how to start a small company or show work that’s not totally normal “plays.” And almost all of the places or series that allowed younger people to figure out their work and approach aren’t around anymore, even compared to when I came up ten years ago. So that’s what’s interesting to me: where would any larger aesthetic—downtown, experimental, etc.—live today? I don’t think the avant-garde is dead, but I think with TikTok and social media idioms being such huge influences now even ostensibly avant-garde work, the “brand” of what was formerly “downtown” is setting off to be really different in the future to come.

The Kitchen though, for me, does operate like some theatrical treehouse or something. The first time I got to work there was not immediately a commission for a big show. What it was—which felt and was incredible at the time—was the offer of several days to just play in the space with tech support [in a residency at The Kitchen in 2014]. Like, even writing that out again—that’s amazing! At that point, I think Lumi Tan had seen several of our shows, so it was a little bit of a getting-to-know-you-more gesture from them, and I was thrilled. So where it felt like it was a treehouse or a clubhouse was that I got all the Half Straddle regulars—actors, costume designer Enver Chakartash, the amazing make-up designer Naomi Raddatz who worked on some shows of ours around then—and we just gathered up lots of costumes, some of my own clothes, some random pieces of art and props, and just brought all of it and everyone up to The Kitchen’s gallery for two days. I convinced my friend Ilan Bachrach (a performer and collaborator with seminal experimental companies Nature Theater of Oklahoma and NTUSA) to bring his nice camera and to film what we were doing and play around with live media and projections. I did have some specific texts we were going to play with, and I’d never had any inclination toward technology (and still don’t)—but somehow since it was the Kitchen I had the idea that this was the place to play with technology more. And the whole thing was also open to the public to wander through and watch. So we did make the space serve that and look aesthetically cool but also we just worked, and didn’t worry about if people were wandering through. Which is weirdly fruitful energy, I found.

What we discovered there with using the cameras and live feed led directly to Ancient Lives, a full show commission about a group of high school girls who de-camp to the woods, make friends with a male witch and set up a feminist TV station—weaving in both references and language from Pump Up the Volume to Emily Dickinson and The Crucible. And, that show—a premiere at The Kitchen at the time it happened for me and the company in 2015—was huge, a big milestone in terms of getting a kind of audience that felt super important to me. Sharing the work with visual art minds, and the contextual frame that got put on my work in general just from being at The Kitchen was really helpful, because it had been a struggle in certain ways for the normcore theater world and press to understand what I was up to. The historical and literal context The Kitchen offered and the kind of theater that had been there recently—like Young Jean Lee, Richard Maxwell—finally gave a proper context to where my work and ambitions sat that was also validating and helpful to me. The Kitchen still does seem to offer that kind of space and time. So, I guess indirectly or directly The Kitchen mandate remains through varying tides of other spaces and zeitgeist of what downtown is or isn’t, and if it is in general/simple terms about playing with form and with rigor, there must be that space and support to be the literal laboratory for that.

I am someone who, in 2019, moved into the mainstream theater space after ten years working in the so-called downtown/contemporary circuit. Do you have any advice to offer or questions to pose in relation to this kind of pivot moment in an artist’s career?

EB: There are the things that provoke major changes in an artist’s career: the feeling of “been there done that,” outside stuff (like a war or a pandemic)—but one thing I must add is poverty. It’s one thing to be poor when you are twenty-five; it’s another thing to barely be able to make ends meet at forty-five. This can have a real effect on what an artist chooses to do. And in some cases, you can be barely getting by while many of your friends are doing very well (that was the situation for me in the early ’80s). It’s impossible for an artist who seeks a better life and a larger audience (don’t we all want that?) not to be attracted by the siren call of the mass media. What interests me is, in a perfect world, is there a there there?

The dynamic period in my career came some twenty-odd years ago when there was no big streaming/cable presence in our lives, not to mention YouTube and smart phones. In recent years, we’ve seen Phoebe Waller-Bridge move from the theater to the mass media with amazing swiftness. And she’s made some damn great work. Is this what you want? Or do you want to make a run at the mass media, and then race back to the theater? That's what I thought I was doing. It didn’t turn out that way. What do you see as a perfect consequence to the attention you are receiving now?

TS: I relate utterly to what you say above. I had a big crisis point just at the time I was just starting to make Is This A Room in 2018. I had achieved a kind of success as an internationally known “experimental theater artist”—I had won several amazing awards and grants, the work had toured to very cool international festivals from Lisbon to Tokyo, and I had become peers and friends with people I had looked up to as artists—but I was totally broke! In the first few months of making Is This A Room, I was temping as a receptionist at this fancy law firm (I hadn’t had to temp in years). I was psychically exhausted, and I felt like a loser who did not know what to do next. I was having a real reckoning with myself over what you articulated about poverty and what one is aiming toward.

I made Is This A Room because I got obsessed with that content and seeing if it could be a stage piece, but really I had no idea it would strike the chord it struck. One tiny secret aim I had with it was to show that I was a good director, something I felt wasn’t seen as much when people looked at the Half Straddle pieces I wrote and directed. Instead, some kind of “weirdo girl auteur” label got put on me around those shows that somehow dismissed both my writing and my directing. And I was literally seeing people have shows on Broadway that had come out of the downtown world around me and I thought, “I’m as good a director as them and maybe I do want to be there and have a bigger audience and maybe better paychecks (any paychecks!).” I didn’t know that this show would actually prove I was a good director or not, but I had a strong idea for it, and it was such a stark show from the beginning that I felt that, if it worked, it would show my bones as a director.

Now I do have a few more opportunities in the more commercial directions—we’ll see what comes. I do want to try TV and movies—my big dream is to make a TV show about being a weird girl theater company in NYC. There’s so much fodder there! I have a proper agent now, which helps … and I’m putting this intention out to the universe. If I’m honest though—the happiest I have ever been while making work was when I made the first totally-did-not-know-what-I-was-doing show at the Ontological-Hysteric Theater, back when Foreman would allow other small works to be there when he didn’t have a show up. That show was the first little speck that put me and my company Half Straddle on the tiny map we’d come to be on. And then making work at The Kitchen—that context feels, even when it’s hard, like I’m in a discourse and in a true communion of effort and possibility. But as you said, as time and age add up, it tips away from the ability to do the never-ending hustle with no sustainable, vaguely comfortable means to show for it. My true dream would be to keep a foot in both places—making theater work that starts and develops at places like The Kitchen but that can move into more commercial spaces like Is This A Room did.

EB: I believe in new ways of making work, no matter how you define “new ways,” because the new ways conform better to the lives of the people who are currently occupying this earth.

Although the academy has endlessly addressed the topic of “downtown” versus “uptown” and experimental versus traditional work, I feel that how new work evolves is more situational than theoretical. In other words, you can say whatever you want, but conditions will trump theory. For example, during the late ’70s it cost very little to live and work downtown. And thousands of young “boomer” artists were migrating to this part of the world after college. This created a massive forge for new work. New work evolves in a “good” way when the work is a function of community (as opposed to commerciality). At that time, thousands of creative souls interacting with one another, inspiring one another, competing with one another (and fucking one another and getting high with one another) led to a good thing: new ways of making work, new kinds of work. It is an unpredictable process but one that is enhanced under certain conditions.

Contrary to what modernists might think, it isn’t a matter of some kind of Darwinian process whereby better art supplants old-fashioned art. That’s ridiculous. There is no evolution in art. But at the same time, you can’t say “well so many great books have already been written, so many great paintings have already been painted, why bother painting any more?”—because each generation’s art speaks to its own sensibility. I can be in awe of the Louvre’s Winged Victory [The Winged Victory of Samothrace (c. 190 BC)] while understanding that it doesn’t speak to my tribe the way it spoke to the Greeks. Art is made, art is studied, and art grows stale. Then new voices, new methods, tuned in to what is happening right now, sprout up and as with all new generations, the new rejects the old. So in my career, I let the work I make dictate the next thing I’m going to make. New opportunities, new media, new facets in my personal life, all contribute to me jumping from one thing to the next.

BIOS

Eric Bogosian is an American actor, playwright, monologuist, novelist, and historian.

Tina Satter is a writer and director for theater and film. She is the founder and Artistic Director of Half Straddle, a critically acclaimed, Obie-winning theater company based in New York City. Since 2008 the company has premiered ten full-length shows and a number of shorter works and video projects that have been seen at festivals and theaters throughout the US, Europe, Australia, and Asia. In addition to Is This A Room, plays she’s written and directed with Half Straddle and toured internationally and nationally include House of Dance, Ghost Rings, Seagull (Thinking of You), and In the Pony Palace/Football, among others. Satter is the recipient of the Foundation for Contemporary Arts and Doris Duke Impact Artist awards. She attended Mac Wellman’s graduate playwriting program at Brooklyn College and earned an M.A. from Reed College and a B.A. from Bowdoin College. Satter has been a visiting artist and/or teacher at Princeton, Yale, NYU, Sarah Lawrence, Hunter MFA Playwriting, University of Michigan, University of Pennsylvania, and more. www.halfstraddle.com.