Credits:

By Elana Engelman-Lado, Fall 2019 Curatorial Intern

October 8, 2019

Mario Diaz de Leon is a NYC-based composer, multi-instrumentalist, performer, and educator whose work encompasses modern classical, experimental electronic, extreme metal, and creative improvised music. Cycle and Reveal, released in September on Denovali, is his fourth full-length modern classical LP. His longtime collaborators include International Contemporary Ensemble, Talea Ensemble, TAK Ensemble, and Mivos Quartet—many of whom collaborated on Cycle and Reveal. Diaz de Leon is also a member of the electroacoustic improvisation trio Bloodmist and a co-founder, with bassist Samuel Smith, of the electronic metal duo Luminous Vault.

In anticipation of his October 24 performance with The Kitchen at Queenslab, we spoke to Diaz de Leon about his work fusing electronic and acoustic sound, his longtime collaborators, the integral role of transformation in his work, and the performance he has designed for The Kitchen’s first event in the Ridgewood, Queens space. For this concert he will be joined by members of International Contemporary Ensemble and Talea Ensemble.

When did you begin to work with electronic and acoustic sound? What led you to explore the confluence of acoustic and electronic sound present in this record, and how do you navigate their distinction?

I started creating electronic music as a teenager, in the mid-’90s. There were underground raves where I grew up in the Twin Cities. It was in a time when that music was having a real heyday. I bought my own synthesizers and started experimenting. I didn’t start writing for classical instruments until I was twenty-one. It was actually at Oberlin, where ICE (International Contemporary Ensemble) was founded around that time. I used electronics as a gateway to hear and visualize acoustic sound, while learning to write for acoustic instruments.

At the same time, I always wanted to keep cultivating being a metal musician and performing electronic music. I wanted to keep growing with the traditions that originally got me into music. So these have been in a kind of dialogue over the last twenty years or so.

Right now, the music I’m performing on guitar and electronics is particularly close to my classical music, and it’s exciting because I can push myself in new ways. I’m often inspired by the level that my collaborators are at interpreting the stuff I’ve written for them, and that gives me a new way to approach my instrument.

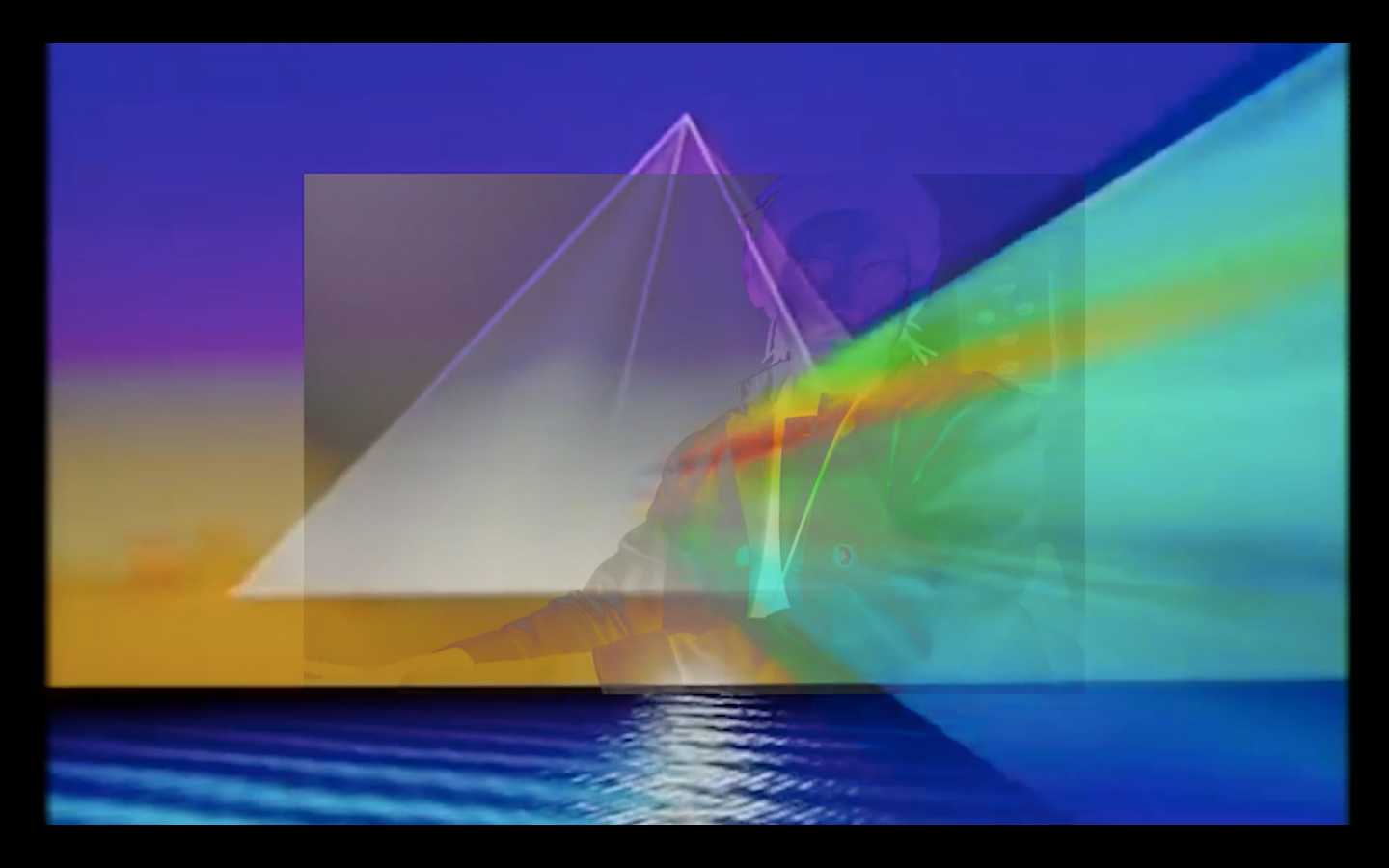

The cover Yuria Okamura designed for Cycle and Reveal “maps and reconfigures” patterns and symbols. How is that process of creating meaning from repurposed or reinterpreted forms, as represented in her artwork, also present in your music?

That phrase [“maps and reconfigures”] actually comes from what Yuria has written generally about her own artwork—that she maps and reconfigures geometric design, alchemical symbolism, occult symbolism, and things of that nature. I don’t mean to speak for her, but I think part of her practice is to freely interpret ancient visual traditions that use geometric design, to reinterpret them in an open space. I really identified with her work in that way when I saw it. I was already using geometric art for the two albums before I started working with her. I love the connection it made because early on, I found a lot of inspiration in studying alchemical diagrams, religious iconography, and found a lot of resonance between the type of music I was making and that world of ideas.

The thing with alchemy is that it’s all about transformation; it’s all about the transformation of materials into a more refined state. In the case of alchemy, the transformation is of what an alchemist might describe as base material into something luminous, into something divine, through processes of decay, reduction, and growth that are tied to the material world. In some ways it resists the medieval Christian idea that matter is dead and the body is corrupt, which of course is a really destructive way of seeing the world. For me it’s more about shifting perspective to reveal what is already there, to see and hear more openly, to cultivate and reveal inner life. It’s sort of a metaphor for personal transformation: that is how I would interpret it. When I approach structure in most of my pieces—whether they’re five minutes long or twenty-four minutes long or a full album–I try to create some type of form that suggests personal transformation, or an experience that has points of climax and transformation that can reveal something, perhaps something that was previously hidden or latent. There are other, more specific musical influences, like certain types of melodies I use that can evoke plainchant. I’m really influenced by the melodies of Hildegard of Bingen. I’m really influenced by certain types of Algerian, Sephardic devotional music that, to me, evoke a sense of longing and something very primal that I like to put into my music. And you can hear that in the album too.

All four titles on the album have some kind of mythical and scientific significance. While playing with multiple meanings, they often inhabit an almost technical semantic realm, for example with “Irradiance” (understood in physics as a quantity or measurement of radiation emitted) or “Labrys” (a double-headed axe that serves as both tactile tool and mythical symbol). Titles can serve as a key for listeners to guide them through the work. What leads you to choose titles with these kinds of multifaceted meanings and symbolism?

Part of it has to do with the fact that I’m making instrumental music that is very heavily characterized emotionally, but isn’t very clear in terms of literal meaning. I have really, really particular associations about what they mean, I’m sure my collaborators do as well. So I try to find a title that’s really resonant, which is always something that’s going to have multiple connotations and not just lean in one direction. In a way it’s related to what we were talking about with Yuria’s work, or ecofeminist theology, the idea of reinterpreting and renewing religious ideas, to use them artistically in a way that suggests new possibilities that are free from dogma. You don’t have to be stuck with the traditional meanings, and in that way the sound and the titles can work together. For example, choosing a title like “Sacrament” for the opening track was part rethinking ways of interpreting that word, a more open approach to what is “sacramental,” which relates to revealing the inner life of sounds, and that being a kind of communion.

Not to use binaries, but this whole idea of working with classical instruments and classical music technique and their long histories puts the work in a dialogue with a lot of traditions, and you can extend the classical instruments in different ways that can suggest even earlier traditions—pre-classical, very primal states. To have that in dialogue with electronic sound is, to me, something that itself has a lot of multiplicity, a lot of resonance. It treats time a bit differently. Rather than thinking about time as always being goal-oriented, per se, or time just moving in one direction, it is thinking of time as more cyclical and recognizing the way the past and visions of the future are in dialogue and always in process. That’s why I choose to work with these iconic titles, things with very charged meanings and histories, that can also be renewed and reinterpreted.

You just touched on your treatment of time. On the album, we often hear tensions in sound—textured and dynamic sonic contrasts that form a soundscape where time feels warped. Sometimes it’s metered, but often it seems more cinched or expansive. Considering also your use of melodic patterning and rhythm, how do you approach time in relation to your work?

On one hand, I work a lot with riffs and repetition, and that comes from a lot of different places. It comes from being a heavy metal musician. It comes from growing up with electronic music. It comes from modern classical minimalism from the 1970s. It comes from working with Afro-American repetition through rock music and heavy metal, in particular longer songs of thrash and extreme metal. On the other hand, there are the more modernistic elements of time in my music that are not as beat-oriented but more freely gestural, and these are informed by spectral music, free improvisation, or melody where time isn’t metered, like Hildegard of Bingen or passages in the Algerian gasba flute music I mentioned earlier. Actually, even the Algerian flute music is often oscillating between areas where it’s freely flowing and areas where the beat comes in and the trance emerges.

Those different areas give me a lot of different types of contrast to work with. I think all of those are heard on the album. I like to inhabit thresholds between different types of time, for me that’s where a lot of magic happens, where I feel like something special is being revealed. I talked about the transformational aspects of alchemy, and there are also transformational ways of working with time. And in terms of how different sections will come together, I’m always looking for that moment where a shift feels like it’s inevitable, where it really either commands attention or it just elegantly dissolves into something else. Very gradual, but very free. And anything between that, it should be elastic, in a way.

On Cycle and Reveal you work with many of your frequent collaborators like members of ICE and Talea Ensemble. What is the role of collaboration in your composition process? How do you feel that collaborative effort influences the sound of your work?

First of all, with collaboration, I think the style is something that I really developed with collaborators like ICE. I’ve been working with them since 2006, and they were always the first people to play these pieces and give feedback. That exchange has been happening for a very long time. There’s nothing more powerful than seeing another person get up on stage and embody a work you’ve notated or a work you put the diagram in, but they [the performers] are the ones that have to make it this physical experience, this temporal experience, and that really put a human dimension to the work. There’s also the process of meeting before we create the piece where we just try out ideas. I can’t emphasize enough how much that informs the actual process. When you’re creating, you’re constantly visualizing and re-visualizing, and having a real relationship with someone collaboratively, as a friend, informs that process.

With this record we did something really special on “Irradiance.” The score doesn’t exist for that piece. Basically, I created a series of electronic loops that were the start of the piece and then got together with Mariel [Roberts]. I said, “okay, we can tune your cello this way.” So she tuned her cello with a low G, but then it was just her listening to the track and interpreting it on her instrument as she saw fit. We would have some dialogue about that, but that’s how we recorded the piece, with her just listening to the track I made. It was really a collaboration, a fifty-fifty collaboration. And a score still doesn’t exist for that piece, so that’s a special one. I’d like to have more collaborations like that.

In the final piece on the album, “Mysterium,” there are sections where the the timing and phrasing of certain riffs that are improvised, and even more than that, all of the amazing coloring and nuance we hear in the notes is Claire, Josh, and Rebekah. All of the piece had been basically scored out, but by the time we got to the end of the piece [when recording] it was pretty much entirely written in the studio. But it had to be that way. At the time I felt strongly that it should be something we discover together in the moment. It was perfect for the album to finish that way because it’s one of the most collaborative moments; it was really touching something beyond.

Actually, it was exactly ten years ago that the debut [Enter Houses Of (2009)] came out. Claire Chase is on that album, Joshua Rubin is on that album, ICE plays on that entire album. I saw an opportunity for Cycle and Reveal to be released ten years later, and I’m so delighted it worked out. It really does feel like a cycle of sorts.

Unlike your previous work with The Kitchen, your upcoming performance will happen at an offsite venue, Queenslab. The concert includes both a solo audiovisual set and performances from Cycle and Reveal by the musicians you collaborated with on this album. Why did you choose this format and how are you approaching this new space?

One thing that’s happening is that I’m opening for the show as performer, which is the first time I’ve done that. I’m at a place right now with my electronic music where it’s really a different realization of the same idea as my classical music. They’re all coming from the same place. To give you an idea of that, first, what became “Labrys” originally started as a thirty-minute electronic work that I’m going to play at the Queenslab space. So people will be able to hear these different realizations of the material. I’m also performing the music under my own name for the first time, whereas the last time I played at The Kitchen, I did it as Oneirogen.

So this [performance] is really celebrating that new interplay of those two things coexisting, and giving the audience an opportunity to appreciate all the connections. They’re still unique, but I think it’s more clear than it has ever been that they’re coming from the same place. And in terms of how we’re using the space—the place has an amazing natural reverb that I’m so excited about. If you’ve heard the album, it’s drenched in reverb, so that’s a great thing. It’s a huge space, so it will feel very expansive. On top of that we’re doing a lot of customizing with how we light it, and there’s going to be a light show that I’m designing for it. I’m excited.