Credits:

By Sarah Cooper, performance program specialist, The Getty, Los Angeles

September 13, 2021

On the occasion of The Kitchen’s 2021 Gala Benefit Honoring Cindy Sherman and Debbie Harry, The Kitchen invited curator and scholar Sarah Cooper to write a text for the series exploring the honorees’ relationships to The Kitchen, with a focus on the 1980 event organized by Edit deAk, Dubbed in Glamour—the event that marked Harry’s first appearance at The Kitchen and crystallized many of the personal and artistic connections that link the musician to both the organization and Sherman.

In November 1980, Debbie Harry, calling in on the telephone, introduced the first rap performance to happen at The Kitchen—or anywhere in downtown Manhattan—when the Funky 4 + 1 closed one installment of a three-night “extravaganza” called Dubbed In Glamour, organized by the art critic Edit deAk. Harry couldn’t be there in-person that night (she wished she had known it was happening sooner), so instead a recording of the telephone conversation between her and deAk played over the PA, and the five young performers from the Bronx took the stage as people in the audience yelled out “Debbie!!,” who was by then an international pop star.

On the call, deAk remarked that this would be the first time the pioneering rap group—a genre that had yet to break into mainstream view from the clubs and neighborhoods of the outer boroughs—would perform live for “this kind of audience,” meaning the downtown art world. It was an audience that was experiencing a particularly heightened convergence between art and music, with a whole community of artists working in hybrid, intermedia strategies with performance and video—multi-sensory tools that readily absorbed the detritus of popular culture. They were artists who found themselves turning more and more to the construct of the rock band as a sharper way to attack the conditions of their moment, gravitating to the freedom of the club over the austerity of the gallery.

Harry had been introduced to rap and the Funky 4 + 1 a few years earlier when Fab 5 Freddy took her and her Blondie-collaborator Chris Stein to the Webster Avenue Police Athletic League to see what Harry describes on the call with deAk as a “big DJ conference.” An enterprising Brooklyn graffiti writer, Fab 5 Freddy had befriended the duo of musicians while working as a cameraman (and sometimes on-screen personality) on Glenn O’Brien’s “TV Party,” a renegade cable access TV show of which Stein was a co-host. In the Bronx, Harry saw the super-fast dexterity of a young Grandmaster Flash on the turntables, and the rapid vocalizations of the Funky 4 + 1, who she described as “street poets” to The Kitchen audience.

In their song “That’s the Joint,” the Funky Four + 1 introduced all the “party people” to their skills, saying “We got rhymes on our mind, we got rockin’ in our heart,'' adding “a lot of things we do, you can call it art.” Alternating between solo personalized verses and unison sections of rhyme, they floored the raving Kitchen audience who begged for more. The group took it from the top and repeated the whole performance a second time for the “overcome manhattanites,” as Live Magazine recapped. The music must have struck a chord with the downtown scene stacked with artists all vying against one another to be the most innovative—not only to create new styles, but to create something completely new in history. In came the phenomenon of rap: it experimented with language and performance. It exhibited a virtuosity and skill executed with an effortless, amateur charm that had no need for validation from any institution. It achieved that revolutionary new art the downtown art community so craved. And it did so without all the affect, pretense, and self-consciousness that plagued the art world.

Glamour is used as uniform: worn and weaponized

Dubbed in Glamour wasn’t an event about debuting rap, however. The reason the Funky 4 + 1 appeared on the stage at The Kitchen was because of their “plus one,” Sha-Rock, who at the age of eighteen was the first female MC. Looking precocious but magnetic in her peter pan collar shirt, she appears to have all the trappings of a shy and demure girl, only to be “shockin’ the whole darn place,” as their song entails, when she takes the mic with complete confidence and utterly upstages her male counterparts. This energy echoed the subversive feminism of the other acts that made up Dubbed in Glamour, billed as three long nights of “fun, extravagance, and spectacle,” including “burlesque, fashion, gymnastics, and other stunts.” DeAk coined these anything-goes moments on stage, which included other music, video, slides, and readings from the “glitterati literatti,” as “image frolics,” and the power and politics of image loomed large.

DeAk poised the event as an “exposé” on a distinct set of women making waves in the club scene, and made a deliberate gesture in carrying over their antics directly from the concept-driven, themed nights at the multi-leveled Mudd Club into the art-world-sanctioned territory of The Kitchen. Described by deAk as “Para-Soho luminaries” in her manifesto-like press release text for the event, these women operated in spaces “geographically and financially marginal to that static institutional bastion, the art world,” even its then-codifying and crowded alternative spaces (“this is the artworld that never had a loft”). And yet “paradoxically,” in deAk’s view, these women were creating with ideas that offered a more ferocious critique that cut closer to the bone of what it meant to be alive in that moment, and exuded in more authentically liberating ways than anywhere else to be found.

DeAk was no stranger to making bold assertions on the nature of art, which she famously did in the newsprint pages of Art-Rite, the rigorous yet witty magazine she published with Walter Robinson from 1973 to 1978 that reoriented the critic’s voice from that of gatekeeping authority to that of the artist’s friend and interlocutor. What deAk was pointing to with Dubbed In Glamour was a tendency that Debbie Harry could be seen as both exemplifying and engedering among the featured Mudd Club coterie, with whom she regularly rubbed shoulders. Harry was not only the face of Blondie—a throwback band that slyly refashioned 1960s girl group sounds into something devastatingly contemporary—but she also inhabited a quasi-space between herself and the identity of cartoonesque “Blondie,” an adorned persona that absorbs the tragicomic tropes of femininity and reflects them back onto the audience.

This self-consciously worn femininity, exaggerated to emphasize its absurdity while being simultaneously fabulous, manifested in different ways during the on-stage offerings at The Kitchen by Cookie Muller and Chi Chi Valenti, who served as hosts, and by Patti Astor, Anya Phillips, Tina L’Hotsky, and other personalities who sang or acted in hysterically amateur fashion. Mudd-regulars Ex-Dragon Debs floated among 120 yards of lavender and black tulle for their “modern cabaret” that included a deadpan cover of Kraftwerk’s “Showroom Dummies.” The electric Lori Eastside, who deAk described as a “champion gymnast, Marvel comix spiderwoman proto-type,” taught “Rockersize,” a poetry-led aerobics class descended into mayhem.

Notably, Nan Goldin shared an early version of her music-set slide show that would become her opus The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, which wrestles with the ambiguity of riveting beauty existing simultaneously in disturbing realities. Harry’s phone call introduction wasn’t her only appearance in the three-day extravaganza: a clip played of her faux-naïf delivery of Fats Waller’s jazzy “Sweet Thing” as the ingénue in Amos Poe’s pseudo-Godard film Unmade Beds, from 1976. Perhaps staged as a sly play on the revolving definition of “new wave,” Harry’s appearance in the film evokes the industry-hoisted origin of the term for the post-punk pop genre Blondie had trailblazed, which came from French cinema of the ’60s.

On view were women whose art was simply being who they were: a nexus of raw authenticity inextricable from complete artifice. DeAk wrote that these women were “masters of cosm-ethic,” wearing their “image as a self-controlled product”—a communication skill women are forced to master taken one step further. They “synthesize the self and environment in highly theatrical terms,” and understand that “taste and fascination is currency,” and “glamour is a seductive, promotional entity.” When deAk writes “Glamour is used as Uniform,” it’s as if she’s speaking directly to the double-persona paradox of Debbie Harry’s Blondie, a quality that makes the rock star in general such an interesting conceit: unlike an actor who embodies a fictional character completely separate from oneself, the rock star lingers somewhere in between their real-self and an exaggerated-self, capable of both parody and verity.

As wielded by the stars of Dubbed in Glamour, this ambiguity in the hand of a woman becomes a way not only to own the appalling expectations and confines of womanhood, but to weaponize them. Harry’s Blondie not only looks back to the cartoon character ideals of the past, but refers to the relentless catcalls of “Hey, Blondie!” on the streets of New York. (A sentiment echoed by the commanding Bush Tetras’s performance in Dubbed In Glamour, singing “I just don't wanna go out in the streets no more because these people, they give me creeps, anymore!”)

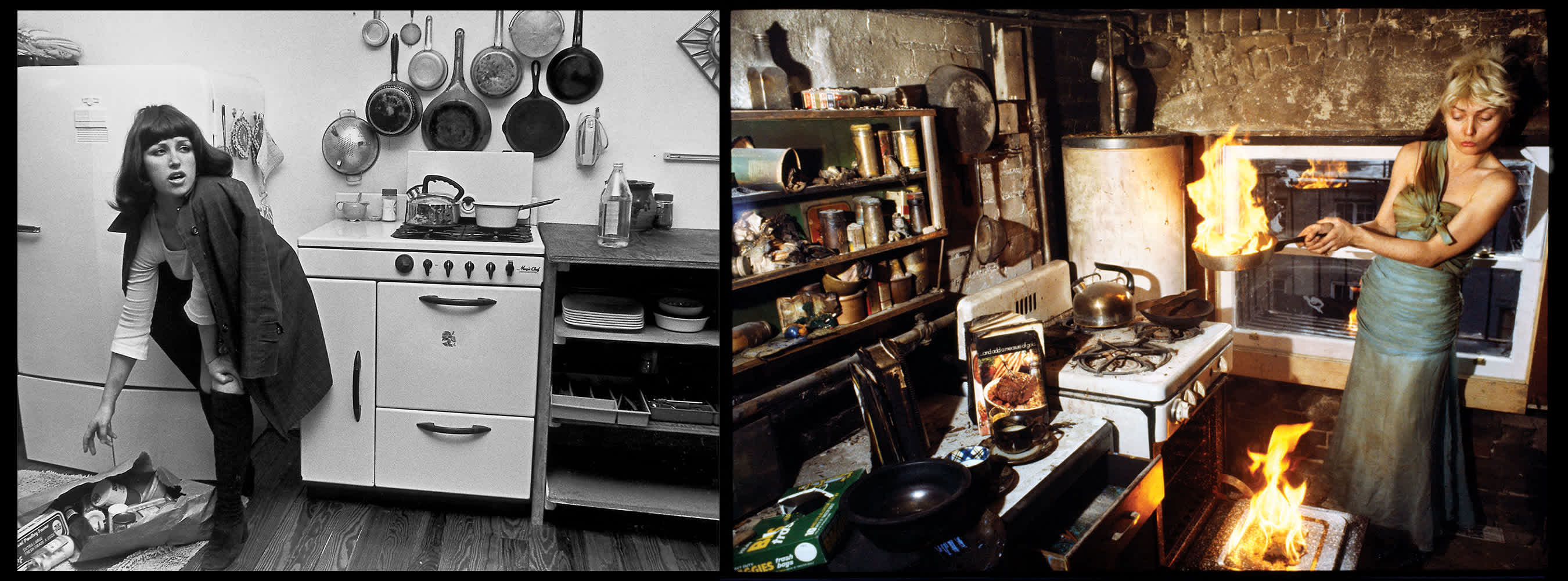

Harry’s vacillating identity echoes the unknowable blonde women inhabiting nondescript scenes in Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills, which went on view in a solo exhibition at The Kitchen in March of 1980, just months prior to Dubbed In Glamour. Like Sherman’s photographs, deAk’s event made the cliches of show-biz its subject and vehicle. “Entertainment,” deAk wrote, “here is reinforced as a true venue to reach out with, as well as the manifestation of self.” She offered up the extravaganza of happenings as “rites of personality-cult,” and dedicated them to “the average American in search of self-image (always settling for entertainment instead).” Sherman’s photographs also speak directly to the image of a woman as she exists in entertainment. All self-portraits but in the visage of an unidentified character, the Untitled Film Stills are taken as if to be scenes from imagined films: the moments are both generic and hostile. Womanhood is isolated and worn as drag—a practice that links back to not only Harry’s formative days, but also The Kitchen’s.

A distinct atmosphere that influenced the whole environment

In 1973, Harry met Chris Stein around the scene of the New York Dolls during their famous residency at the Mercer Art Center—the decaying hundred-year-old hotel converted into a series of ballrooms—in the Oscar Wilde Room, down the hall from which The Kitchen was founded and operated by Steina and Woody Vasulka. Harry and Stein circulated among a set of interlocking figures experimenting across the Mercer spaces, notably the glitter-covered enigmatic performer Eric Emerson, whose band The Magic Tramps invited in and performed with the Dolls, and with whom Stein later became roommates. Emerson knew the Vasulkas from Warhol’s scene and Jackie Curtis’s drag musicals like Vain Victory, for which they built sets, played as musicians, and documented on video. The Vasulkas used their Portapak camera to capture Emerson, encrusted with glitter head-to-toe, as part of a series of counterculture clips they called “Perception,” from 1971, which they screened in the upstairs room of Max’s Kansas City, where a young Harry was working as a waitress. The Vasulkas regularly lent The Kitchen’s keys to drag ballet troupe Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo, while other figures like Wayne County, Tomata Du Plenty (later of L.A.’s The Screamers), and former members of the extravagant drag theater The Cockettes circulated the Mercer’s ballrooms and surrounded the Blondie-duo early in their formation.

Steina Vasulka described the Mercer as a “culturally and artistically a polluted place,” which made it an interesting home for The Kitchen. She and Woody were “interested in certain decadent aspects of America, the phenomena of the time: underground rock and roll, gay theater and the rest of that ‘illegitimate’ culture.” [1] “We were aware of the New York Dolls performing,” recalled Robert Stearns, who became director of The Kitchen in 1973. “They were such a freak act, you couldn’t miss them,” he added in an oral history for The Kitchen. “We thought we were doing weird stuff but the Dolls made our clan look like eggheads from Columbia University.” He couldn't help but wonder if the band helped create “a distinct atmosphere that influenced the whole environment.” The Village Voice called David Johansen of the Dolls “an absolutely fabulous combination of Mick Jagger and Marlene Dietrich,” and the confusion between their heterosexuality and camped-up, cheaply constructed flamboyance became part of their allure. In this climate, wearing a constructed gender was a fluid strategy between queer and straight alike, a means to attack and reject mainstream society’s oppressive expectations.

Harry and Stein formed Blondie in the New York Dolls’s image: an early ’60s girl group, with simple tunes as innocent as The Shirelles or The Shangri-Las, raised from the crypt of their bygone suburban childhoods, only to emerge into the urban wasteland, their Sunday-best in tatters, disillusioned, lascivious, and male. In an issue of Punk Magazine, Lester Bangs wrote that for Blondie, the ’60s girl group functioned as a readymade, ripe for exploitation, as it did for their future CBGBs bill-mates The Ramones, for whom the Dolls’s Mercer residency also served as a catalyst. [2] The Dolls donned an aesthetic of cast-off trash, exposing the lie inherent in glamour while absolutely reveling in the seduction of it. They refashioned the American experience as a sublime ruin, reflecting a generation and a crumbling city left to “drop dead” by its authorities. Translated through Blondie, we are shown another great ruin of the time: the ideal subservient woman, a platinum blonde. [3]

One of deAk’s stars of Dubbed In Glamour, Anya Phillips, infamous for her skin-tight fashions and who engineered several of Harry’s iconic looks, dressed James Chance in flashy retro suits to further exaggerate his parody of masculinity during his physically confrontational performances with The Contortions. Like Harry and Sherman’s donning of accentuated gender stereotypes, Phillips styled Chance as classic big-band man—a provocation of dressing up like “Dad,” the musical forefathers of rock’n’roll, only to pry open “the standards” as the band’s sets dissolved into inappropriate and pathetic bouts of violence.

"We are prospectors of slum vintage," deAk once wrote. "We have taken your garbage all our lives and are selling it back to you at an inconceivable markup."

By including Harry in Dubbed in Glamour, deAk implicitly acknowledged the influence of that Dolls moment at the Mercer Arts Center and their exploitation of gender as drag, mapping how strategies of self-image played out across the previous years and informed the Mudd Club personalities. [4] DeAk even enlisted drag performer Angel Jack, formerly of the Cockettes, to be the star performer at the Dubbed In Glamour after-party at the Rock Lounge. The Kitchen event also mapped a progression from deAk’s landmark program PersonA, held at Artists Space across four days in November 1974. There deAk asked a series of artists who would come to define performance art—Chris Burton, Vito Acconci, Adrian Piper, Laurie Anderson, and, notably, the infamous practitioner of decadently decaying camp, Jack Smith—to investigate the theme of autobiography. Whereas the artists’ own stories made interesting material for their art then, Dubbed In Glamour marked deAk’s observation that their material had metamorphosed into pure personality.

Harry’s championing of the Funky 4 + 1 to the downtown art world would send reverberations through its ranks for years to come, just as the New York Dolls had at the outset of the ’70s. [5] Fab 5 Freddy would extend his creative network beyond his “TV Party” friends and become a regular presence at The Kitchen, and after spearheading several events, joined its first national performance tour in 1982 as a signature Kitchen figure. A few months after Dubbed in Glamour, when Harry served as host of Saturday Night Live on Valentine’s Day 1981, she invited the Funky 4 + 1 to perform in what would be the first rap performance on television in history. At this nascent moment for rap’s introduction into the mainstream, Blondie released their hit single “Rapture,” featuring Harry performing several verses of rap, which in the hands of the ’60s revivalist band earned the truly singular phenomenon of creating an instant-pastiche of a genre yet to achieve nostalgia. This moment marked the ushering in of an era in which artists—like “TV Party” and Mudd Club-regulars Jean-Michel Basquiat, Kenny Scharf, and Keith Haring who incorporated hip-hop culture into their work—would take Dubbed In Glamour’s prophecy that the role of the artist would converge with celebrity to extreme ends.

BIOS

Sarah Cooper is the performance program specialist at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. She has organized programs featuring artists and musicians including Kim Gordon, Brendan Fernandes, Lonnie Holley, Martin Creed, Midori Takada, Helado Negro, David Wojnarowicz, Derek Jarman, and Solange Knowles. In addition, Sarah has held positions at the Museum of Modern Art and the Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Royal Academy in London, and the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. She holds a Master's Degree in Art History from Hunter College, New York. Her thesis, Expanding Experimentalism: Popular Music and Art at the Kitchen in New York City, 1971–1985, explores the creative output of artists’ bands and the relationship between popular music and avant-garde performance practices.